In 2026, the University of Ottawa Heart Institute celebrates its 50th anniversary. It’s a milestone not just of medical achievement, but of the people, ideas, and determination that built one of Canada’s largest and foremost cardiac health centres from the ground up.

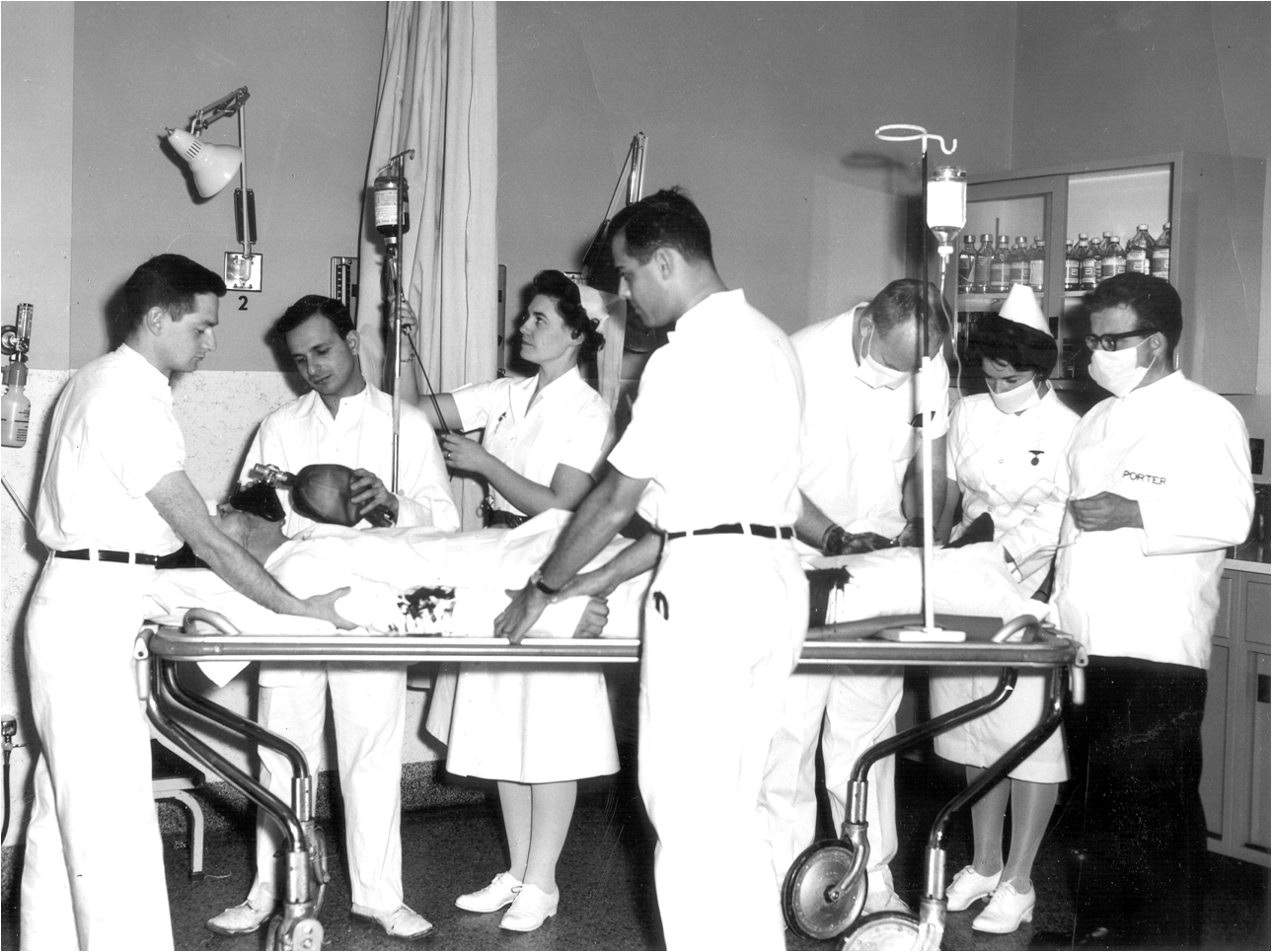

The early years of the Ottawa Heart Institute were modest: borrowed space, makeshift offices, and small teams working long hours with limited resources. Yet, from the outset, its founders brought complementary strengths and a shared vision. Dr. Wilbert J. Keon, a pioneering cardiac surgeon believed Ottawa could set a new standard in heart care—one that united exceptional patient care, transformational research, and the training of future generations. With Dr. Donald S. Beanlands, a giant in Canadian cardiology, by his side, they began the journey.

This was never about opening a building but about creating something that would endure.

From humble beginnings

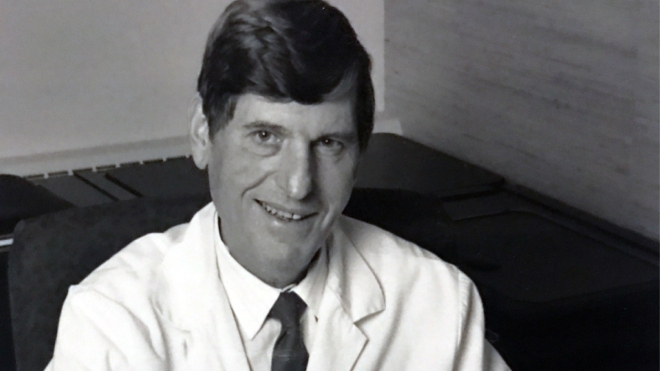

For Dr. Lyall Higginson, one of just six full-time cardiologists at the Heart Institute in the early 1980s, the earliest days were defined by possibility.

In an interview with The Beat, Dr. Higginson recalled walking past empty studs where the Coronary Care Unit would one day stand. Despite fumes drifting into the cath labs from the fresh blacktop in the parking lot above, Dr. Higginson said the vision to be a world-class heart institute always felt within reach.

“There was no ceiling to what we believed we could achieve, so long as we were willing to work for it,” he said.

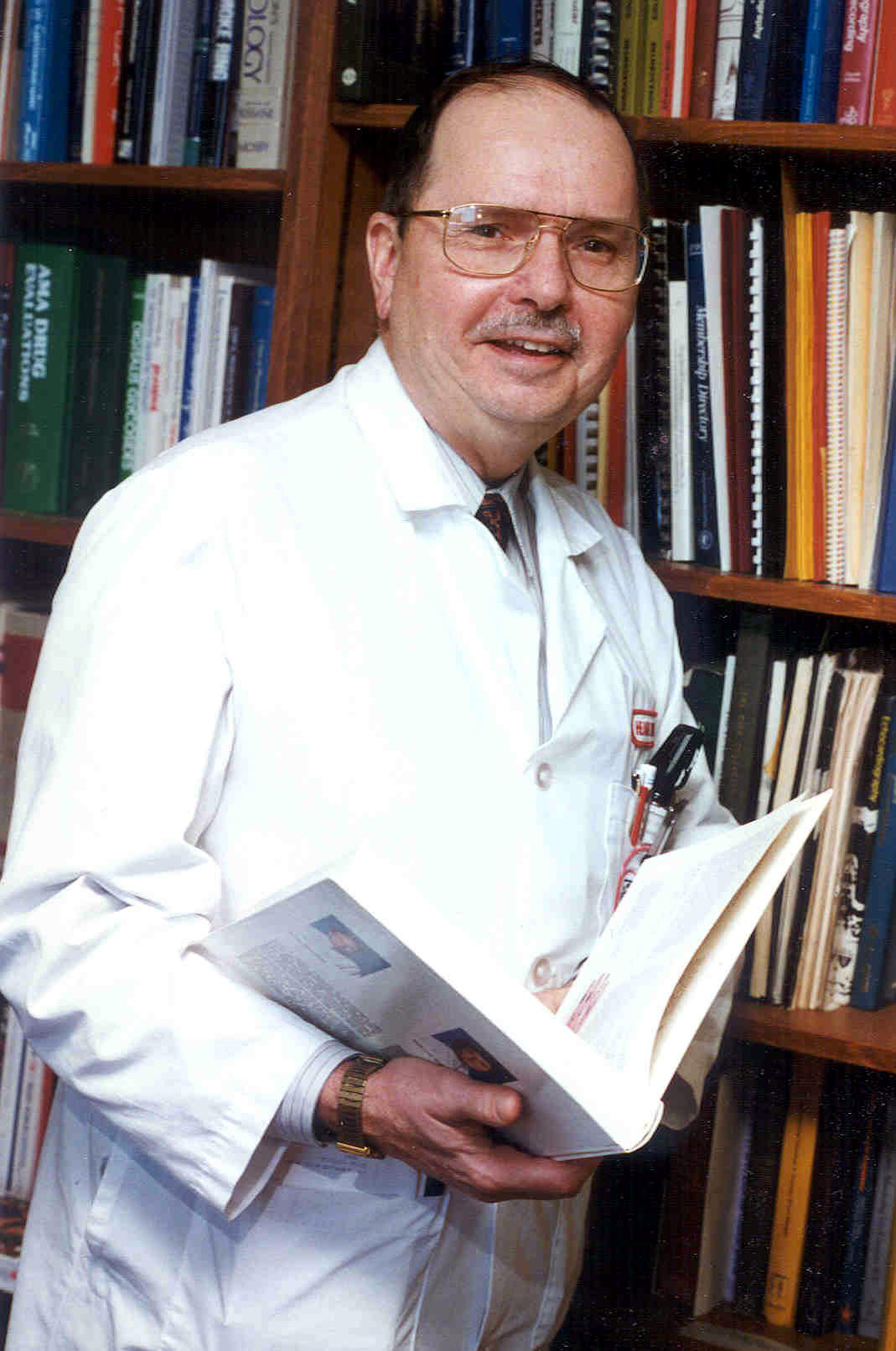

A few years later, that same sense of possibility drew Dr. Ross A. Davies to Ottawa.

Fresh from Yale in 1980 and in his early 30s, he arrived to launch a nuclear cardiology program. At the outset, however, there was not even space for a nuclear cardiology imaging camera – no small undertaking for an institute still finding its footing.

“When I arrived, the Heart Institute was more idea than infrastructure,” Dr. Davies recalled. “Dr. Don Beanlands’ office was in the East Lawn Pavilion, a former wing of the Ottawa Hospital for veterans. I remember him smoking a pipe back when that was allowed.”

Practices have changed dramatically since those early days. The shift reflects a deeper understanding of cardiovascular risk and the importance of prevention, shaped in large part by the leadership of Dr. Bill Dafoe, who directed the prevention and rehabilitation program at the Heart Institute from 1982 until 2003; and from Dr. Andrew Pipe, who is today recognized as one the world’s leading experts in smoking cessation. Dr. Pipe’s work led to the widely adopted Ottawa Model for Smoking Cessation, developed at the Heart Institute and now used around the world.

Dr. Davies’ office was far more rudimentary.

“There was no office, no lab,” he said. “Just a phone on the floor.”

Despite these limitations, Dr. Davies worked closely with architects and colleagues to design nuclear cardiology and stress-testing laboratories for the new building above the catheterization labs. He oversaw the purchase of the Heart Institute’s first dedicated nuclear cardiology camera, and under his leadership, the program became a national leader.

For Heather Sherrard, who joined as a nursing coordinator in 1988, the early institute was a place of constant ingenuity. As healthcare evolved, so too did the Heart Institute, she said, expanding “like a rabbit warren.” Day units were carved from staff lounges; electrophysiology labs squeezed onto the first floor.

“Every new program—PCI, stents, minimally invasive surgery, transplants, VADs—was carefully planned,” Sherrard said. “There was never a project for glory. Everything was about doing the right thing for patients.”

Over the years, Sherrard and other early leaders grew alongside the Heart Institute. Sherrard would later become executive vice president and chief nursing officer, helping shape both clinical programs and organizational strategy until her retirement in 2020.

Together, these pioneers built more than programs. They forged a culture rooted in collaboration, creativity, and the pursuit of excellence.

Culture and vision driving early success

Dr. Higginson said that culture came from the top. Drs. Keon and Beanlands believed, surgery, cardiology, and anesthesia should operate as a single, cohesive team. Shared changing rooms encouraged daily interaction across disciplines. “I shared lockers and saw these colleagues every day,” Dr. Higginson said. “From the very beginning, it was collegial.”

Trust became the foundation. “If you weren’t aligned with that culture,” Dr. Higginson said, “you didn’t last long.”

Innovation thrived in this environment. Dr. Davies introduced a medication that safely increased blood flow to the heart, enabling testing for patients unable to exercise, and helped secure approval for specially trained technologists—not just physicians—to administer it. These protocols were rapidly adopted across Ontario and Canada.

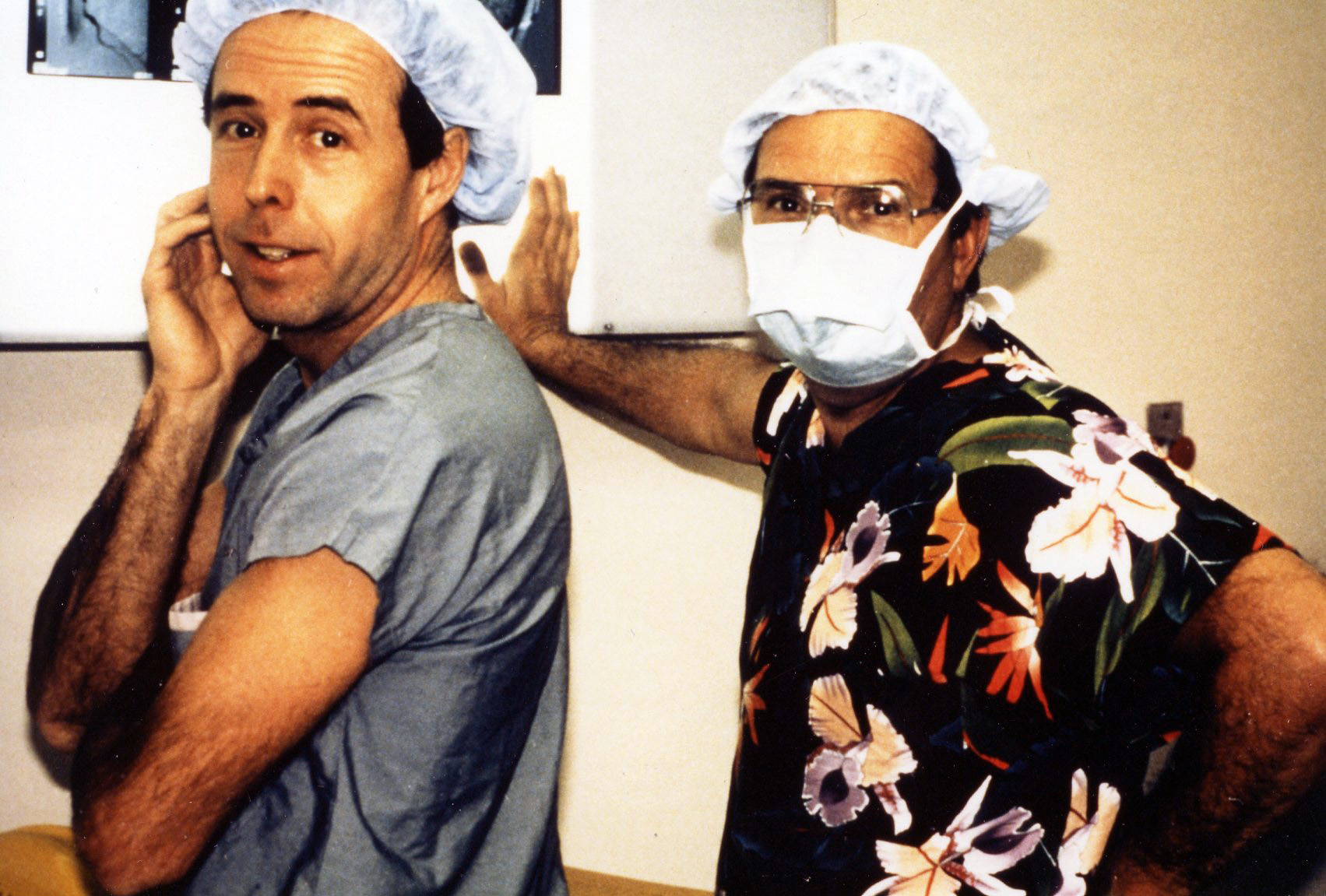

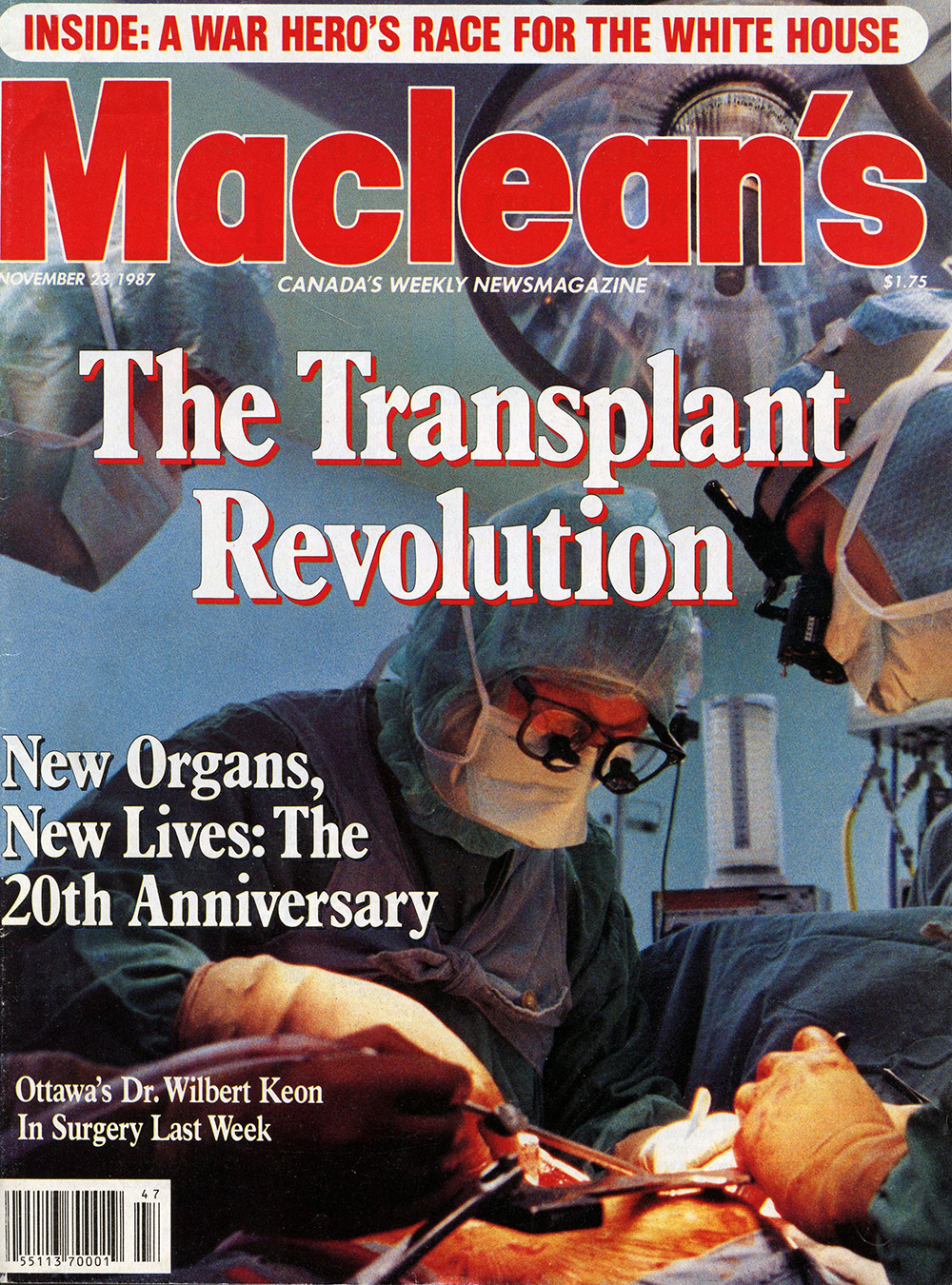

Surgical milestones followed as well. Dr. Keon performed Ottawa’s first heart transplant in 1984, with Dr. Davies serving as medical director. “We built the transplant program from scratch,” he said. “The first 11 transplants were all successful, which was unprecedented at the time.”

Dr. Davies recalled a conversation with the program’s first patient, who insisted on undergoing transplant surgery in Ottawa rather than at more established centres in Toronto or Montreal. The choice, he said, was a clear vote of confidence in the Heart Institute’s ambition, emerging expertise, and the leadership of Dr. Keon.

The transplant was a success, though in those early years, the work was far from seamless.

Dr. Andrew Pipe, then a surgical assistant once raced through the hospital with a donor heart packed in what was essentially a beer cooler. The heart was destined for a patient who had received Canada’s first Jarvik artificial heart as a bridge to transplant, performed by Dr. Keon. “I remember when he tried to get into the operating room, security wouldn’t let him in,” Dr. Davies said. Moments like these were stressful and depended on people across the institute working together to overcome unexpected obstacles.

“Everyone knew each other well,” Sherrard said. “You could speak openly in meetings, and outside the room, you were united in support.”

The quiet proof

Recognition did come, though it was never the goal. In 1991, Princess Diana visited the Heart Institute to open the Day Unit, meeting with patients and staff.

A royal visit was distinction enough. Still, those who were there say the true measure of the Heart Institute’s vision was far quieter. It revealed itself in the everyday care of patients, the training of future clinicians, and a culture driven to give everything for patients without expectation of fanfare.

Over five decades, the Heart Institute has transformed cardiac care—from beta blockers and early pacemakers to stents, minimally invasive surgery, TAVI, gene testing, and remote monitoring. Thousands of residents and fellows have trained within its walls. Its reach now spans Northern Ontario, Newfoundland and Labrador, Quebec, and even remote communities like Iqaluit.

Yet the original pillars remain unchanged: patient care, research, and education, each reinforced with a shared belief that anything is possible when everyone works together.

“What’s remarkable is how consistent the vision has been,” said Dr. Rob Beanlands, the son of Dr. Donald S. Beanlands and now the Heart Institute's president and CEO. “The tools have changed, the science has advanced, but the commitment to patients, research, and education is the same. We’re still building on what our founders believed was possible.”

The Ottawa Heart Institute is celebrating 50 years of heart in 2026. Visit our anniversary webpage!

Never miss a Beat

Want interesting stories like this delivered straight to your inbox as they happen?

Subscribe to our mailing list